Phil Hutchinson and Rupert Read consider the public policy of sex.

The policy of sex? Isn’t sex a private matter? Well, we here discuss where this seemingly quintessentially private matter intersects with public policy, with a view to developing better informed public policy.

So, just where might this intersection be located? Well, here are one or two proposals: sex-work and the public health management and clinical treatment of sexually transmitted infection. We will take the latter of these two as our primary focus. There are certainly a number of other areas in which one might claim to find sex and policy to be closely related, but for now we restrict ourselves to sexual health policy. We treat these topics as distinct in the main, because we would suggest that in many ways they are so; but there will be important areas of co-concern, as we shall see.

Put simply, there are two ways one might be inclined to go, when faced with policy decisions emerging from the sex/policy intersection, which might have their basis in one’s broader political dispositions. One might be inclined to legislate the private and think in terms of behavioural prohibitions, controls and constraints (of the legal variety) or, alternatively, one might be inclined to respect the sanctity of the private and think in terms of liberalisation beyond the current cultural mores (here one might be open to a proliferation of constraints of a different variety). Which way would consideration of our five parameters direct us?

1. PRECAUTION. The first of our parameters, precaution, might, given ordinary usage, suggest prohibition, control and constraint. If an infection is sexually transmitted then prohibiting or restricting sex, or the kinds of sex – e.g. specific acts and specific patterns of sexual behaviour – might seem like the obvious way to exercise precaution. But what if there is a choice here?

Specific sexual acts carry greater risk of the transmission of infection. Some sexually transmitted infections have far greater likelihood of transmission via vaginal intercourse than via, say, oral sex, and even greater likelihood via anal intercourse, other things being equal. Also, certain patterns of sexual behaviour might increase the chances of contracting an infection. Patterns of sexual behaviour involving multiple partners can increase the chances of contracting an infection, over monogamous sexual relations, just as monogamous sexual relations bring greater risk than abstinence. But such reasoning isn’t alone the source of an inclination to prohibition, control and abstinence here. For precaution can be exercised through means other than blanket abstinence and/or prohibition. Legislating or seeking to restrict behaviour is but one option. We might explore other options, which seek simply to make the behaviour less risky: condom use, prophylactic use (both pre and post exposure) where available and regular sexual health screening are all ways in which we can make sex safer without intentionally subjecting sex to constraint.

The inclination to think in terms of behavioural prohibition, restriction and abstinence always draws on more than purely precautionary reasoning. It rather combines precautionary reasoning with a particular moral agenda, perhaps latent, that treats certain sexual acts and certain patterns of sexual behaviour as suspicious, deviant or just plain evil. Indeed, there is some evidence deemed through comparative studies of societies which pursue prohibition and control, and those that pursue other, non-prohibitive, precautionary policies, that prohibition and control as policy is not only morally-inflected (if not loaded) but ineffective as a precautionary policy. There are grounds for believing that it is, in fact, not merely ineffective but counter-productive (See for discussion and detail the section on evidence below).

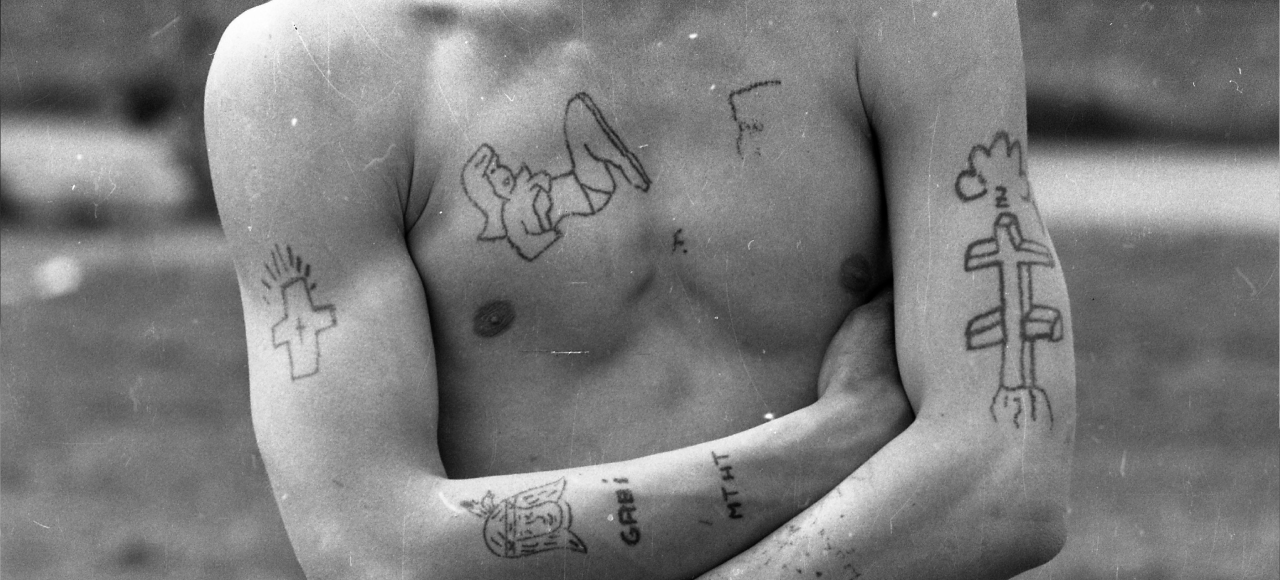

A serious problem with policies that seek to prohibit or control is that they serve to stigmatise that which is prohibited (and this is a function of the moral aspect of policy which seeks to legislate and control behaviour). Stigmatising people, and enshrining that stigma in law which prohibits certain acts and certain patterns of behaviour (or the promotion thereof) on precautionary grounds, inclines most individuals to avoid anything that might serve to associate them with that which is prohibited and stigmatised. Furthermore, another problem with prohibition – a way that it can self-defeat – is the extent to which in some contexts, such as drug-use and some sexual subcultures, representing something as illicit can make that thing more appealing.

If that which we need to be precautious about is the possibility of sexually transmitted infection epidemics, then, crucially, we need to avoid stigmatisation and provide means of taking precaution which do not smuggle in moral attitudes that militate against openness.

2. EVIDENCE. So, what evidence might policy be based upon? We have alluded to it already, in our reference to the comparative studies, which show that policies of prohibition, control or abstinence campaigns often lead to increases in STI rates.

But let us get into some detail. Let us here take the example of HIV. The HIV virus can be transmitted by a variety of means, via various bodily fluids, including semen, vaginal fluids, rectal secretions, blood or breast milk, but not saliva. An individual living with the virus, who is on successful antiretroviral therapy, will be likely to have a fully suppressed viral load, meaning that the virus is undetectable. Evidence continues to emerge which appears to show that an individual with a fully suppressed viral load is incredibly unlikely transmit the virus to a sexual partner.

So, to get the spread of the virus under control we need to ensure that the virus is not transmitted via those bodily fluids. Here are the options: (i) introduce policies and laws which at a behavioural level seek to minimise the pathways to infection: these have typically taken the form of public health messages which are designed to frighten people by emphasising the danger the virus poses (tombstones etc.), emphasising that sex is risky, particularly with people you’ve just met, and so on.

Alternatively, (ii) ensure access to antiretroviral therapy for those with the virus, thus enabling them to live with a fully suppressed viral load. Further, educate people about the transmission pathways of the virus so that they understand how to take precautions. For example, one can prevent transmission through establishing a physical barrier by use of a condom or one can, in the case of HIV, do it chemically, through what we might think of, very loosely, as a “bio-chemical condom”: pre-exposure prophylaxis (tenofovir/emtricitabine PreP), which works by combating the virus, including in the bodily fluids through which it is most commonly transmitted, thereby preventing it from gaining a foothold.

This is where we need the evidence, and we have some. The evidence is that fear messages work in the short term, but in the long term produce side-effects which can ultimately offset their good short-term effects. Because fear-messaging serves to stigmatise those with the virus, or who believe they might have the virus, by implying they did something risky and they are now, if they have the virus, dangerous. Moreover, such messaging is often targeted at groups considered to be high-risk. While this is sometimes welcomed and requested by those groups, it also serves, by association, to stigmatise the group through creating a link between the group and the virus (danger) and the behaviour that leads to contracting the virus (risky). (E.g. a link is created in the public imagination between being a gay or bisexual man and being risky and potentially dangerous.) So, while of course pathways to infection should be minimised in the sense of people acting and seeking to act responsibly, wearing condoms, etc., nevertheless, in terms of public policy, pathway (ii) is much better supported by the evidence than pathway (i).

If society makes very public claims (such as through public health messaging) that to be the bearer of a particular property is to be dangerous and to have been careless then that is likely to militate against people coming forward to be tested (they fear that merely by coming forward they are in effect saying that they have subjected themselves and others to risk and thus will be identified as dangerous: a very publically stigmatised group). As one can see from the evidence collected on this in Norman Fowler’s recent book AIDS: Don’t Die of Prejudice, the stronger the fear message gets and the more the marginalisation of certain groups is in a society, the more this mitigates against controlling infection rates. The promotion of fear and the association of certain groups with that which is to be feared leads to fewer people coming forward for testing, because to do so is to indicate one has failed to heed the warnings and engaged in risky behaviour; and, further, that one is potentially a member of the now stigmatised group. Add to this the fear and shame associated with becoming, as the messaging tells you, dangerous. If that society has also introduced legislation such as anti-gay laws then things get even worse.

This said, it is, therefore, unsurprising that contemporary Russia has increasingly high infection rates. Prejudice kills; that’s what the evidence tells us.

3. POLITICAL ECONOMY. How does public policy around sexual health affect the politics of a society; who or what does it empower or disempower, politically or democratically (or otherwise)? Who or what does it empower or disempower, economically? The answer to these questions is not obvious. But we would make a couple of preliminary suggestions:

(i) One needs to guard against sexual disease and death becoming an excuse for large corporations to make obscene profits. The drugs needed to facilitate antiretroviral therapy for those with HIV need to made affordable / brought within the purview of the public health system. This is a particularly pressing worry right now, given that sexual health in the UK is being funded by local authorities as part of the public health budget, and that the government are due to make £200 million worth of public health cuts this year. Decisions about where these cuts are being made is down to each local authority. Given that local councils have no responsibility for long-term care emerging from sexually-transmitted infections, they have unfortunately no financial incentive to invest even in provenly effective preventative public sexual health, and so, facing harsh financial stringencies, they will very likely divert funds elsewhere. (This is of course, incidentally, another argument in favour of having a truly national NHS – as we set out in a previous instalment of the Five Parameters.)

(ii) One needs to be wary of any public policy intervention that will create hostility to those who may already be struggling in society. This was already indicated in (2) above. And it takes us directly to (4):

4. ASYMMETRY. How does sexual health impact upon those whose voices don’t or can’t get heard? This parameter is in the present case fairly closely aligned with the 3rd parameter, above. For here we might consider two forms of asymmetry.

First is the asymmetry that comes from having policy formed which is inflected by a certain moral view. Here the voiceless may be those who do not subscribe to that particular view on sexual morality, or those who are depicted as immoral from the perspective of the dominant moral viewpoint. For example, the current debate about HIV PreP, is strongly inflected, indeed created, one might argue, from there being in-play certain moral attitudes towards sex, where those arguing against PreP do so because, they believe, it will encourage people to have more sex. One might just as readily, from within a different moral framework, view enabling people to have more sex as a good thing.

Second, and relatedly, asymmetry emerges from groups being stigmatised. It is a function of stigmatisation, that the stigmatised group’s voice becomes (further) marginal(ised), thereby creating asymmetry.

In summary: a clumsy public health policy on sex risks being a silencing policy. And of course, as we have said, silence risks being death, hereabouts.

5. FRAMING. While one should remain open to the thought that all considerations are morally inflected, the specific nature of the moral inflection is what serves to frame the discussion. If the discussion is framed by a heteronormative monogamous Christian or secularised-Christian attitude to sex then that will steer the emerging policy proposals in a certain way. Such policy proposals will, for example, not be designed with a view to better enabling or facilitating the living of a polyamorous lifestyle, but will be likely to see such a lifestyle as part of the problem and curtailing that same lifestyle as, therefore, an important part of the solution. The policy proposals will not, for example, be likely to empower sex workers, but rather see the answer in further criminalisation of sex work.

However, here is where things may get trickier. For the very frame of “sex-work” might itself be questioned. Is “sex-work” work just like any other work? Just like office-work, or what have you? A possible lurking danger here is that the liberalisation of sexual mores and the overcoming of prejudice around sex, so vital (we have suggested) for public health, could turn into commodification, and this is something we might consider too high a price to pay, as it were. That is: if, in the name of overcoming prejudice (not least against “sex-workers”) we allow that sex-work should indeed be construed as simply work, and then (presumably) legalise it, are we aiding and abetting the treatment of something intimate and private as something else? As with the stigmatising side-effect of fear messaging discussed above, we need always to be wary of the unanticipated consequences of well-intentioned policy.

The challenge this yields, we believe, is this: can an attitude of non-moralising openness around sex, which we have suggested is crucial in relation to public health, be sustained while avoiding the production of the side-effect of the commodification of sex and bodies (and, if it can, then how)? To answer that question would require a further article, perhaps another walk through the five parameters. We’ll simply note here that there are various efforts in play to tread this path: most famously the “Nordic model”, which attempts to strike a bold, feminist-inspired compromise, in essence criminalising the commodified buying of sex but not its selling by the provider. Thus the “sex-worker” is not stigmatised or punished. In sum: framing considerations complexify somewhat the line we have been taking in the current piece. For the values and frames that the outcome of parameters 1 through 4 appears to favour may be problematic. We believe that it is wrong to facilitate the complete commodification of sex, and to turn the private into something fully public. This is not moralism. It is ethics, it is one strand in feminism, and it is a political philosophy of how public policy doesn’t necessarily mean the elimination of the private sphere. Should one believe that there needs to be protection of the private sphere from state (political) interference then one needs to ask themselves whether that same sphere needs protection from market obliteration.

Conclusion.

The considerations adduced under (5), above, complicate things somewhat. But it will nevertheless be clear to the reader where the general line of our argument is headed. Thinking through the five parameters makes pretty clear that, on balance, a public policy vis-a-vis sexual health that seeks only to prohibit, moralise and scare is not an intelligent public policy, certainly in the twenty-first-century context. Let’s in summary run swiftly through the five parameters again, to see why:

What is the weight of the five parameters, when it comes to the question of sexual health and public policy? On this question, unlike some others that we have looked at earlier in the series, precautionary considerations, while sometimes clearly salient, are nevertheless not as decisive as they are in some other cases. For, while sexual health is of course quite literally a life-or-death matter, it is surely most unlikely to destroy a whole society. If epidemics such as HIV are left largely untreated, that can have enormous negative societal consequences: such as approximately 300,000 excess deaths in South Africa, as a result of Mbeki’s HIV-denialism. But unprecautious action in this connection, unlike in relation to (say) nuclear weapons, is not at all likely to be ruinous: human extinction is simply not on the agenda in this connection. For, sexual ill-health of its very nature (i.e. due to its transmission route) not able to move fast enough to be an utterly ruinous pandemic.

Similarly, considerations of political economy and asymmetry, which we have suggested in previous articles are weighty indeed in cases such as nuclear power (when it is authoritarianism and large corporations that will tend to benefit from a pro-nuclear policy, and given that it is distant future generations who will have to clean up our mess) are less weighty in the present case. For, while we suggested above that asymmetry- and political-economy- considerations probably point toward the conclusion we are tending to urge in the current piece – that public policy around sexual health should be heavily oriented toward making it possible to treat sexual health as a public policy concern, openly and without prejudice – they are again not decisive. For public sexual health is not primarily about aiding the truly voiceless (those at asymmetric risk from decisions made by those in charge), and whatever we decide about it is not going to turn our polity into an out-and-out totalitarian regime or something similarly undesirable (i.e. it will not be determinative, so far as “political economy” is concerned, nor so far as our overall assessment is concerned).

By contrast, evidentiary considerations, which are less decisive in cases we have previously considered – such as nuclear weapons, and geo-engineering – are pretty decisive here. By now, we have fairly clear evidence of which sexual health policies work and which don’t. And, as we put it just above, a key to the overwhelming importance of this is the following key “self-reflexive” point: it turns out to be crucial that one is able to have serious sexual public health policy, in order to prevent or adequately treat (for example) the kind of widespread misery and suffering that the HIV epidemic brings. And thus a basically “liberal” rather than a basically “prohibitive” policy is indicated.

The framing fly in the ointment suggests that, as ever, any issue worth devoting thousands of words to is never simple, never uni-dimensional. What we see in the present case is three parameters which tend to point in the direction that is decisively indicated by a further parameter that, in the present case, is, we believe, the weightiest of all: evidence. Given this, the fifth parameter’s complexifying effect might seem unwelcome. But hey, we never said things were going to simple. This is public philosophy. It’s not rocket-science: in many ways, it’s much harder than that.

Phil Hutchinson is Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at Manchester Metropolitan University. He is the author of Shame and Philosophy, and blogs at The View from the Hutch

Rupert Read is Reader in Philosophy at the University of East Anglia. He is the author of several books, including Philosophy for Life, and Chair of Green House.

They are founder members of the ThinkingFilm film as philosophy blog.

For this instalment in the Five Parameters series the authors were helped by detailed comments from: Rageshri Dhairyawan, Sara Paparini, Matt Phillips and Shema Tariq.

You might also like...

Subscribe to The Philosophers' Magazine for exclusive content and access to 20 years of back issues.