Claire Creffield moves in the direction of a constructive conversation between atheists and believers.

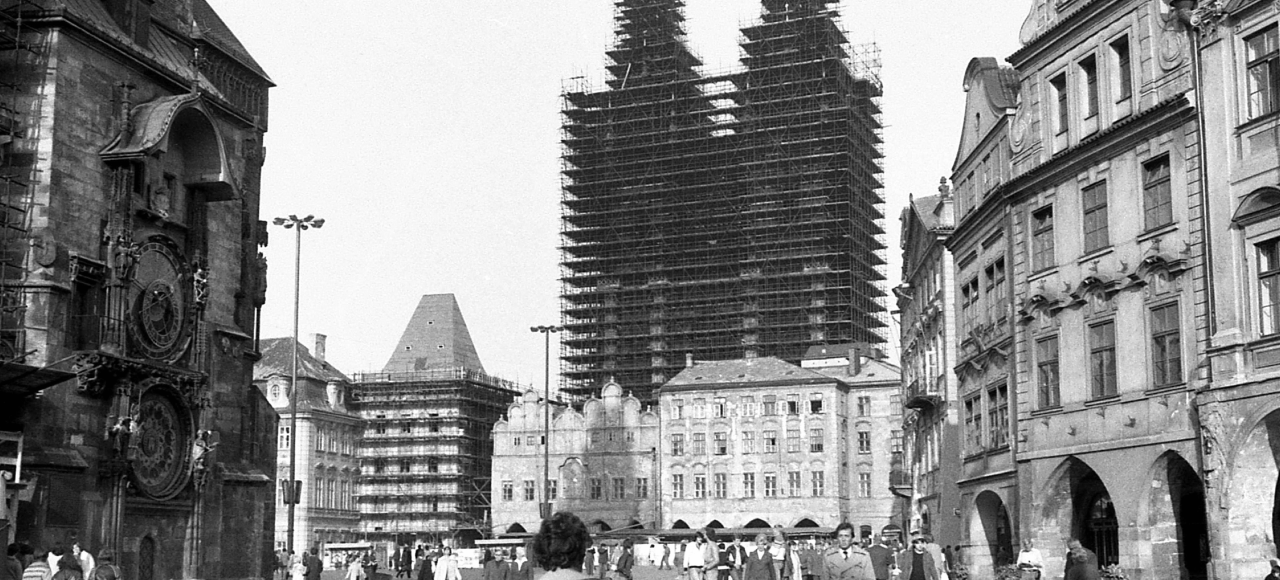

I didn’t warm to Alain de Botton’s suggestion, in his book Religion for Atheists, that we should start building “atheist temples”, because not far from my house there is already a splendid one. Among its many beautiful features are several columns made of Frosterley marble, crammed with highly polished fossilised corals. The presence of these fossils invites the viewer to see the building (which itself took forty years to complete) in the context of 325 million years of our planet’s history, during most of which we were absent. But if that timescale makes us feel insignificant, the fossils also call to mind a huge cultural achievement – the theory of evolution that enables us to understand our own origins. Being made to reflect on that scientific achievement while admiring the architecture of a building that is rich in art and craftsmanship and history encourages a seamless appreciation of all of our scientific and creative attainments. The building is also a testimony to the labourers who built it. And it houses a memorial to other local labourers, miners who died in accidents. For all these reasons and more it is a celebration of humanity, even though a significant minority of the people who use it are seeking to celebrate God.

The building is Durham Cathedral, a place of Christian worship. And although de Botton is very sensitive to the resources that religious buildings offer to the non-believer, he thinks that for an atheist such a building is a flawed resource. He thinks that atheism requires brand new buildings, which evoke some of the sentiments that a cathedral might evoke, but which explicitly exclude God from their design. The reason for this is that he wants to separate what he regards as religion’s good bits from the taint of belief in supernatural entities. The good bits of religion are the resources it gives us for learning lessons in living: how to be kind, how to honour community ties, how to see ourselves in a light that gives us understanding of and consolation for our suffering, weakness, and failures. These resources, he says, are not essentially religious. They have been “colonised” by religion and we need to take them back. What is essentially religious, according to de Botton, is a belief in the supernatural. Religion cannot abandon that, he implies, and so atheists cannot benefit from the resources religion offers in support of living a good life unless these are explicitly separated from their religious context, by means of a slightly bizarre process of innovating atheist doppelgangers of religious infrastructure.

I want to suggest that this process of separation and innovation is misconceived. Durham Cathedral, and all of the trappings of religion, are fully available to me as an atheist, and I would lose something rather than gain something if I visited one of de Botton’s new atheist temples instead. This is because religion itself, and not only the trappings of religion, can be a resource for atheists.

To see this, we need to start by noticing that the term “atheist” is not as simple as it might appear. Though it appears to consist in a single negative statement (“There is no God”), it actually involves a range of possible claims – about what religious people mean when they say there is a God, about the relevance and nature of supporting evidence or argument for God’s existence, and about how we can assess the meaningfulness (or lack of meaning) of religious language. This means that there is not, in fact, a single atheism, but a range of atheisms, some of which are more hostile to religion than others.

Think first of all about what religious people are trying to say when they claim that there is a God. There is no monolithic consensus here, and since atheism is a negation of whatever that claim about God’s existence might be, we shouldn’t expect atheism to be monolithic either. Many of the most vocal atheists like to focus on a particular sort of claim of God’s existence – the claim that there is a god who created the universe and whose nature and intentions are part of the explanation of the universe. At its most extreme, this sort of belief in God contradicts established scientific theories, notably the theory of evolution. And it is contradicted in turn by an atheism that says that such an assertion of God’s existence can only be established on the basis of experimental evidence that is in fact lacking: all of the available evidence suggests explanations for the world that do not involve God, so the hypothesis of God’s existence is unwarranted and almost certainly false.

But there are also plenty of religious people who are content to look to science alone to explain the way the world is. They accept evolutionary theory without reserve and rely on physicists, not theologians, to unlock the secrets of the universe. For these people, God’s creative contribution is just an initial self-effacing impulse, simultaneously willing the world and delegating it in its entirety to science. Since their assertion of God’s existence does not contradict any scientific accounts, it cannot be judged false on the basis of the truth of those accounts.

A philosophically minded atheist might respond to this version of the assertion that God exists by calling it, not false, but meaningless. A statement is only meaningful if there is some way to determine whether it is true or false, they might say, and there is no set of circumstances that would count towards the truth or the falsity of the claim that such a scientifically redundant sort of god exists.

This sort of atheist is invoking the “verification principle”, which has an origin in Wittgenstein’s early thought. His theory of meaning in the Tractatus makes religious propositions meaningless: the world is the totality of scientific facts, and no proposition is meaningful that does not correspond with a scientific fact. But Wittgenstein was far from sharing the scathing hostility to religion that today’s atheism exhibits, and we can look to his thought to supply a different sort of atheism altogether, one that can foster an allegiance – perhaps even an identity – with some kinds of religious faith. It is worth making a sketch of his thoughts about religion, not so much with the idea that they are a correct or coherent philosophy of religion, but to show the availability, to an atheist philosopher, of a project of seeking value in religion, and even truth, albeit not truth of a profoundly satisfying kind.

Three features of Wittgenstein’s thought come together to suggest that atheism can be deeply at home in religion: he thought that the religious outlook manifested something very important; he thought (eventually) that religious discourse, including discourse about God, was meaningful; and he thought that religious discourse was founded in universal human characteristics, shared by both people of faith and those without faith.

The importance of religion struck Wittgenstein strongly even when he thought of religious utterances as meaningless: “There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical.” When we try to talk of God, we knock up against the limits of language, and our efforts are cognitively fruitless. But that is not to dismiss religion. Philosophy, too, knocks up against the limits of language, and is not thereby destroyed (though it has to be reconceptualised, with a much more modest agenda). In the case of both philosophy and religion our inclination to run up against the limits of language shows us something important.

What does it show us in the case of religion? It shows us something about our status as beings in the world, capable of seeing things only from the midst and not from the outside, much as we cannot see our eye in our visual field. The inarticulable and impossible view from the outside is not available to us, but it is something that we seek: “It is not how things are in the world that is mystical, but that it exists …. To view the world sub specie aeterni is to view it as a whole – a limited whole. Feeling the world as a limited whole – it is this that is mystical.”

Science alone tells us “how things are in the world”. In this sense, Wittgenstein is an atheist. But there is a certain – mystical – orientation which seeks to reflect with wonder on the world viewed as a whole, sub specie aeterni, which Wittgenstein does not reject (he merely calls it unsayable).

To try and make sense of this, think for a moment about those religious believers mentioned above for whom God’s role is limited to an initial act of creative delegation, which sets the scientific ball rolling. And remember also that the religious doctrine of free will also sees God as delegating to individuals the whole of their inner lives. A god who so copiously sloughs off all of his agency over matter and persons is infinitely small, in the sense of being nowhere present in an account of how the world is. The difference between such an infinitely small god and no god at all is not in the world. It does not tread on the territory of science by concerning itself with “how things are in the world”. Seeing such a god as present or absent is not a disagreement about facts: it is something more like seeing the world under a different aspect: faith and atheism are like different ways of seeing the same picture, and the disagreement between them is something like an aesthetic difference of opinion – concerning matters to which religious people and some atheists are compellingly drawn.

According to Wittgenstein’s earlier thought, religious discourse, despite its importance, is meaningless. Those for whom the mystical/religious orientation to the world is important could make it manifest in their way of life, but they could not speak of it without uttering nonsense. However, as his thought developed, he gave a new account of language. Instead of having the uniform scientific function of naming objects in the world and asserting facts about the world, he argued, language has meaning by being embedded in diverse human practices – including scientific discourse, but also including the practices of those who share a sense of the importance of a religious/mystical orientation. Language is pluralist, and among several very different possible uses of it are those that meaningfully express, in their “deep grammar”, the unsayable. His atheism remained, in that he denied that propositions involving the word “God” can be interpreted as meaningfully asserting the existence of some entity. But he presents such propositions as meaningful nonetheless, entirely capable of being uttered without error, as the linguistic components of a certain way of life, one which he seems to have admired.

So, religion is both important and meaningful for Wittgenstein. But what did it have to do with him, as an atheist? Wittgenstein was both engaged with and cut off from religion. He did not join in religious practice, and the religious practitioners of his day would not by and large have felt it possible to accept his account of their enterprise. He was an outsider to the religious practices of mid-twentieth century Europe. But does that mean he did not partake at all in the religious “form of life”? It cannot mean that, not only because he was so clearly drawn to religion, but also because on his new account of meaning, meaning is generated within our shared practices: it is our participation in a shared form of life that makes it possible for us to share a language. If a religious practitioner and a non-practitioner did not have a relevant form of life in common then they quite simply wouldn’t be able to talk to one another about religion at all.

In tracing the origins of religious language and ritual, Wittgenstein speaks in terms of fundamental, universal human characteristics. Humankind is, for Wittgenstein, by its very nature ceremonious, given to ritual, so a religious form of life has been persistent throughout human history. And human thought and language, by its nature, is mystical: it draws us to its limits, to the kind of attempted utterances of religion and philosophy that Wittgenstein spent his life seeking to clarify and dissipate. There is, then (underlying the historically specific and transient forms of religiousness that individuals may and may not endorse), a universal religious consciousness, shared by believers and non-believers alike (though more highly motivating for some than for others) – in virtue of which there can be meaningful conversations between believers and non-believers. That religious consciousness, or form of life, does not entail a belief in God: it is the framework within which God’s existence can be meaningfully asserted or denied. When God’s existence is finally denied altogether, as it is in vast swathes of modern society, our religious consciousness becomes a “post-religious consciousness” – godless, but still part of a trajectory determined by the conditions which gave rise to religion in the first place. We don’t entirely escape religion just by negating it: atheism is a stance adopted towards religious questions, rather than a disappearance of the religious form of life.

This is our plight, this loss of God coupled with a continuing participation in the form of life which gives religious discourse its meaning. The mystical, as defined by Wittgenstein, persists, but those who are drawn to it find that there is nothing that can be satisfactorily said of it: religious language, though meaningful, is grounded in nothing other than our human mores. Where do we go from there?

Some of us are quite content to turn attention away from the limits of language back to the scientific. But others will continue to be driven towards those limits, and, perhaps surprisingly, they will find that religion itself gives expression to the loss, the absence of God, and is possibly at its most beautiful when it does precisely that.

Perhaps the most poignant religious expression of the loss of God is that moment within the Christian story when the sense of loss is projected onto God himself, in the person of Jesus Christ crying out “My God, why have you forsaken me?” The same loss is replayed in numberless Christian artworks. The aria “Erbarme dich” in Bach’s St Matthew Passion, for example, speaks of a yearning for God that is so intense that the spirituality is located more squarely in the yearning than in the (nonsensical, non-existent) entity which is superficially its object. One might object that in Christianity as traditionally conceived that loss of God is transient, it is the prelude to a reunification with him. Well, yes. But our religious consciousness evolves with our scientific and philosophical discoveries, and our interpretation of Christian mythology evolves accordingly. A story that was once about our separation from and reunification with God can equally well serve as the expression of a sense of separation that reaches its culmination not only in the death of Christ, but also in the death of the idea of a transcendent God, by means of which death we are acquainted with a painfully less satisfying, but immediately present, divinity, located nowhere other than in our shared religious observances. This would be a form of atheism that is either deeply friendly to religion, or actually religious itself. I’m not sure that it matters much which we call it. This form of atheism would be enriched by a stroll around a cathedral which is empty of God but saturated with the practices by which religious meaning is generated.

Claire Creffield works in academic publishing and is a former fellow of All Souls College, Oxford.

You might also like...

Subscribe to The Philosophers' Magazine for exclusive content and access to 20 years of back issues.