In the midst of a viral pandemic, the summer of 2020 saw protests decrying police brutality and demanding racial justice on an unprecedented scale in the United States. What you think of these protests will likely depend on which news sources you pay attention to and how seriously you take the president’s Twitter account. A widespread – although false – narrative among many conservative media outlets and Republican politicians portrays the protests as out-of-control threats that have pushed America’s urban centres to the brink of collapse. This narrative is ethically problematic: it can encourage reactionary violence, and at least sometimes involves deliberate deceptiveness. It’s also epistemicallyproblematic: it can lead the white majority to inappropriately discount the testimony of protesters, while simultaneously wronging that same majority by entrenching their false beliefs and making it harder than it needs to be for them to understand the truth.

Sparked by the death of George Floyd – who was killed by a Minneapolis police officer kneeling on his neck for nearly nine minutes – people took to the streets in the summer of 2020 in hundreds of cities, suburbs, and small towns across America. While specifics vary, protesters are advocating for a wide range of concrete changes – ranging from holding specific officers accountable for their wrongdoing, to reforming how police departments operate, to defunding police departments and reallocating the funds to other causes, to radically reconceptualising the role of police. According to the New York Times, protests occurred in more than 40% of U.S. counties. With an estimated 15 to 26 million people participating between late May and mid-June, this was the largest political demonstration in U.S. history. The movement is continuing strong, as protests have been ongoing for well over 100 days in many large cities.

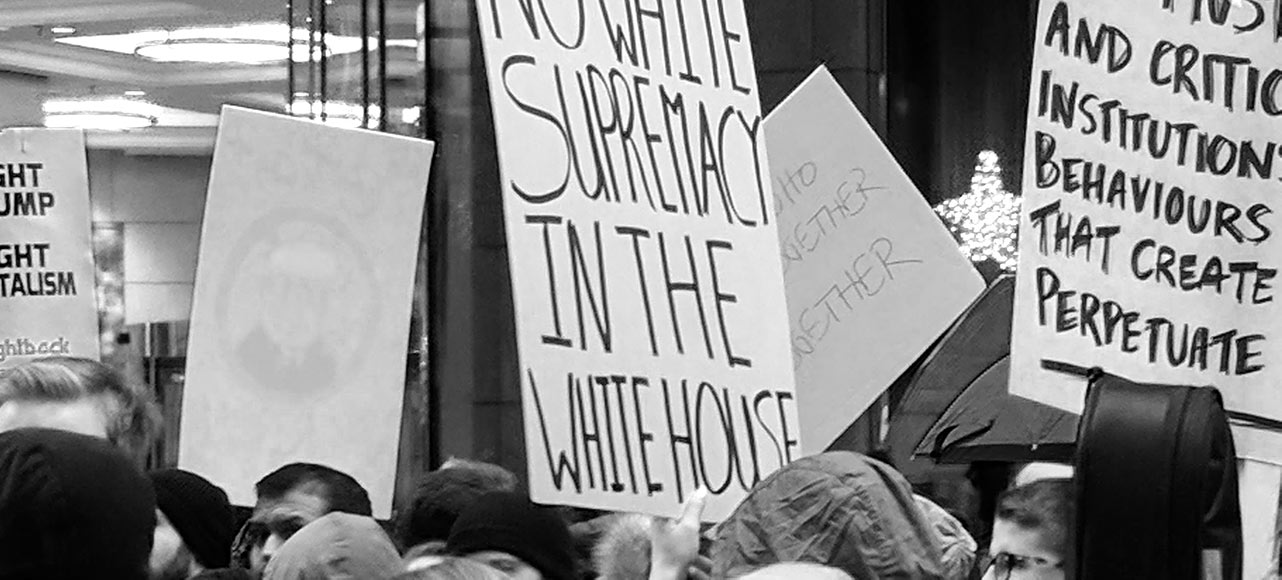

Inflammatory reports in traditional and social media and from the Trump administration have characterised these protests as nothing more than reckless rioting. In a speech on June 1, Trump stated that “our nation has been gripped by professional anarchists – violent mobs, arsonists, looters, criminals, rioters, antifa and others.” He has continually raised the spectre of violence and destruction spreading to the sanctuary of the suburbs. For example, on September 10, Trump tweeted that “If I don’t win, America’s Suburbs will be OVERRUN with Low Income Projects, Anarchists, Agitators, Looters and, of course, ‘Friendly Protesters.’” These narratives are shaping public opinion: 42% of respondents in an early June poll agreed that “most” Black Lives Matter protesters “are trying to incite violence or destroy property.”

It is true that there has been vandalism, property damage, and violence stemming from or cooccurring with some of the protests, especially at night. Protesters have sprayed graffiti onto storefronts, federal buildings, and monuments. Rioters – sometimes affiliated with the protests, sometimes opportunists taking advantage of chaos – have broken windows, looted goods from stores, and set fires to cars and businesses, including small and minority-owned businesses. People have thrown things at police officers and occasionally thrown punches. Most tragically, The Washington Postreports that as of late August, 27 people were killed in incidents that were connected to the protests, although most identified perpetrators were not protesters and some deaths were only tangentially connected.

We should not ignore or minimise these real and sometimes extremely serious harms. But we must also recognise that such harms are the exception rather than the rule, and that the narrative that Trump and others are pushing is false. “Professional anarchists” don’t exist. Protests have been driven by local grassroots groups; they aren’t funded by elites or planned from the top-down. The suburbs have been largely untouched as serious civil unrest has been mostly confined to small areas of large cities.And the overwhelming majority of the protests – nearly 93%, according to a report compiled by ACLED, an NGO that tracks and analyses political violence – have involved no violence or property destruction whatsoever. Most protesters have obeyed the law, or have engaged only in non-harmful acts of civil disobedience aimed at drawing attention to their cause, such as blocking traffic.

It is not always clear who instigated violence or property destruction or what their motives were. In some cases, agent provocateurs or far-right extremists have attacked protesters or spurred others on, such as the “umbrella man” in Minneapolis who smashed windows to incite looting and was later identified as a member of a white supremacist organisation. In many more cases, police officers themselves have been the primary instigators or escalators of violence, lashing out with disproportionate and brutal force at anti-police brutality protesters. Police have, among other things, targeted protesters and journalists directly with rubber bullets and other projectiles, thrown protesters to the ground, and indiscriminately deployed tear gas on crowds, which is a chemical weapon banned in war.

Overall, the racial justice protests of the last few months are not the nefarious threat that they are frequently made out to be. This misleading portrayal is ethically problematic in multiple ways. First, framing protesters as rampaging revolutionaries might inflame tensions in ways that lead to concrete harm. Overstating the threat posed by protests might incentivise people to take actions that increase the risk of violence; for example, armed counter-protest groups have urged people to go on patrol to “defend” their cities, as Kyle Rittenhouse did in Kenosha, Wisconsin before killing two people.And crucially, focusing exclusively on the most sensational and dangerous elements of Black Lives Matter protests steers the conversation away from what really matters. This risks drowning out or distracting from protesters’ legitimate calls for justice and reform, which can hinder meaningful progress.

Second, surely some politicians and news outlets are deliberately framing the protests in exaggerated ways as a ploy to score political points or garner viewers, clicks, and ad revenue. Such cynical fear-mongering is intrinsically morally wrong regardless of the consequences it leads to. Deliberately misleading the public about an important topic for your own personal gain is disrespectful; it violates Kant’s categorical imperative, which requires us to treat others as autonomous agents capable of making their own decisions rather than using them as tools for our own purposes without their consent. It’s also selfish and dishonest, and not something an upstanding politician or journalist would do.

Third, misleading portrayals of the protests can lead to what philosophers call epistemic injustice. Miranda Fricker developed and popularised a theory of epistemic injustice in 2007, although the roots of the concept can be found in earlier Black feminist thought. Epistemic injustice involves harming someone as a knower, or unjustly damaging their capacity to know the truth and successfully share this knowledge with others.

One of the main types of epistemic injustice Fricker identifies is testimonial injustice, or giving someone an unjust credibility deficit – that is, not taking what they say as seriously as you ought to – because you’re prejudiced against them. Framing political protests as senseless riots may lead to increased testimonial injustice against protesters and their supporters, as it risks delegitimising or undermining their reliable narratives about what their goals and tactics are and how the police have been mistreating them. This is especially likely to occur if protesters belong to stereotyped groups. And while this summer’s BLM protesters have been racially and economically diverse, the dominant cultural image of a BLM protester is that of young, urban, working-class Black person, about whom prejudicial attitudes are widespread.

Misleading portrayals of the protests might also lead to epistemic harms of a broader, more subtle, and more surprising sort. Widely disseminating and legitimising false narratives can lead to what I call ignorance bolstering, or the fostering of an environment in which it is much harder than it ought to be for people to know the truth about important topics. While our ignorance can be bolstered about anything, ignorance bolstering is especially pernicious when the truth is difficult to accept – say, because it doesn’t cohere with someone’s existing beliefs or challenges a cherished self-conception.

While testimonial injustice stems from prejudice and targets oppressed groups, ignorance bolstering is likeliest to affect the privileged. For example, rich people are most likely to be led astray by the misleading myth that the American economic system is fully meritocratic, while men are most likely to have their ignorance bolstered by patriarchal victim-blaming for sexual assault. And people with white and upper-class privilege are least likely to themselves be victims or direct witnesses of police brutality, which makes them most susceptible to having their ignorance shored up by misleading narratives about anti-police brutality protests.

Ignorance bolstering is not as serious a wrong as is testimonial injustice; it’s much worse for an oppressed person to be inappropriately disbelieved than it is for the (perhaps wilful) ignorance of the privileged to be fortified. But the epistemic harms of ignorance bolstering are nevertheless genuine and widespread. Making it needlessly challenging for people to believe the truth about an important topic makes it harder for them to properly understand the world and their place in it. This disrespects them and makes them worse off as knowers. Ignorance bolstering also indirectly harms the marginalised, since it can lead the privileged to commit epistemic and material harms against them – consider economic elites who vote against progressive taxation because they believe the poor are not hard-working, or men who inappropriately discount the testimony of women who report sexual assaults.

In other work, I explore how police officers frequently claim to have feared for their lives as an alleged justification for shooting unarmed and unthreatening Black people. Widespread acceptance of unmerited fear as an excuse by the legal system, police unions, and the media can bolster the white majority in their ignorance, making it easier to maintain the false and dangerous belief that police use of force is generally justified.

Unrealistic narratives about this summer’s BLM protests can contribute to ignorance bolstering about police violence in a similar way. Framing protesters as nothing but violent criminals bent on destroying traditional American values and lifestyles makes it more challenging for people understand why protesters are angry and what kinds of changes they are demanding. Because these demands challenge the status quo, they are likely to be perceived as a serious threat among those who benefit from the stability of that status quo or are aligned with those who so benefit. Accordingly, these demands are likely to be met with great resistance, which makes ignorance bolstering about this topic especially insidious.

For example, consider what it implies when words like “rioter” or “thug” are used to describe everyone present at an unruly protest. These words draw on deep-seated racist narratives connecting Blackness with criminality or dangerousness to portray all protesters as uncontrollable threats. And the way to respond to an uncontrollable threat is not to engage with it and learn from it, but to manage it or control it, with violence if necessary. Accordingly, it is easy to dismiss – and thus remain ignorant of – the demands of “rioters” and “thugs.”

Or consider how “antifa” – which is a loose label describing a wide range of autonomous organisations and individuals that oppose fascism and white supremacy using mostly non-violent but sometimes militant methods, and who haven’t caused violence at protests – is spoken of as if it were a single organisation with centralised leadership employing terroristic tactics. City councils and state legislatures and voters should be listening to protesters and grappling with their demands. But if protesters are just “antifa terrorists,” we’re all off the hook: there’s no sense in negotiating with terrorists.

A major source of ignorance bolstering stems from how “violent” has been used to describe protests that have involved no harm or threat of harm to any living things. For example, on June 26, Trump issued an executive order about protecting federal monuments. While the text of the order makes passing reference to actual violence, it focuses primarily on damage to statues and memorials, with most of the specific examples involving only graffiti. The order accuses state and local governments of having “surrendered to mob rule, imperilling community safety, allowing for the wholesale violation of our laws, and privileging the violent impulses of the mob over the rights of law-abiding citizens.”

Property destruction is indeed harmful. But not all harm is violent harm, and conflating harm to bodies with harm to buildings risks muddling our perceptions of what is happening at protests and whether police responses are appropriate. Damaging a monument may or may not be justified all-things-considered, but it is not violent. As Nathan Robinson argues in Current Affairs, calling the destruction of objects “violent”lends justification to the dangerous idea that it is proportionate for police to respond to destruction of property with force against people: after all, they’re simply fighting violence with violence.

I have not used the word “peaceful” to describe the 93% of protests that have been non-violent and non-destructive. This is because I think framing protests as “peaceful” risks contributing to ignorance bolstering in two ways. First, stressing the peaceful nature of racial justice protests might imply that violence or destruction is the norm for such protests, such that non-violent protests need to be specially identified as such. But Black Lives Matter protests are generally non-violent as a rule.

Second, the word “peaceful” can carry misleading connotations. When Trump was elected in 2016, I spent my next introductory ethics class at a small Midwestern university talking with my students about their questions and concerns. One reaction surprised me. Anti-Trump protests were occurring in cities around the country, and multiple students expressed great fear that these protests were, in their own words, “not peaceful.” But at least in our city, there hadn’t yet been any news reports of violence or property destruction; the police hadn’t even tear-gassed anyone. The protesters were angry,though: they shouted and cursed, pulsating with hurt and fury. And my kind, sincere, and unfailingly polite students perceived this as being “not peaceful.”

The dominant image of a “peaceful” protest is that of a non-disruptive protest – of protesters who don’t scream or swear, who don’t get in the faces of cops, and whose slogans the most powerful and dominant groups in society can find “inspiring” rather than “divisive.” The BLM protests of this summer have not been peaceful in this sense, and with good reason. Effective protests are fuelled by righteous anger at injustice; they involve language that is meant to shock us out of complacency and forms of disruption that are impossible to ignore.

What do protesters mean when they chant “No justice, no peace”? The chant is not charitably read as a threat of violence. Rather, it is a proclamation that protesters will not prioritise calm and civility at all costs: that they will be willing to be loud and disruptive enough that they force even the most complacent to pay attention. It is a proclamation that they will not, to quote Martin Luther King Jr.’sLetter from Birmingham Jail, prefer “a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” As we strive to seek this sort of positive peace, we must be on guard against ignorance bolstering, and remain vigilant about which narratives we’re paying attention to and what they imply.

Alida Liberman is assistant professor of philosophy at Southern Methodist University. Her research focuses on theoretical ethics, practical ethics, and the space in between, as she seeks to understand concepts in ethics both for their own sakes and for how they can help us grapple with real-world problems.